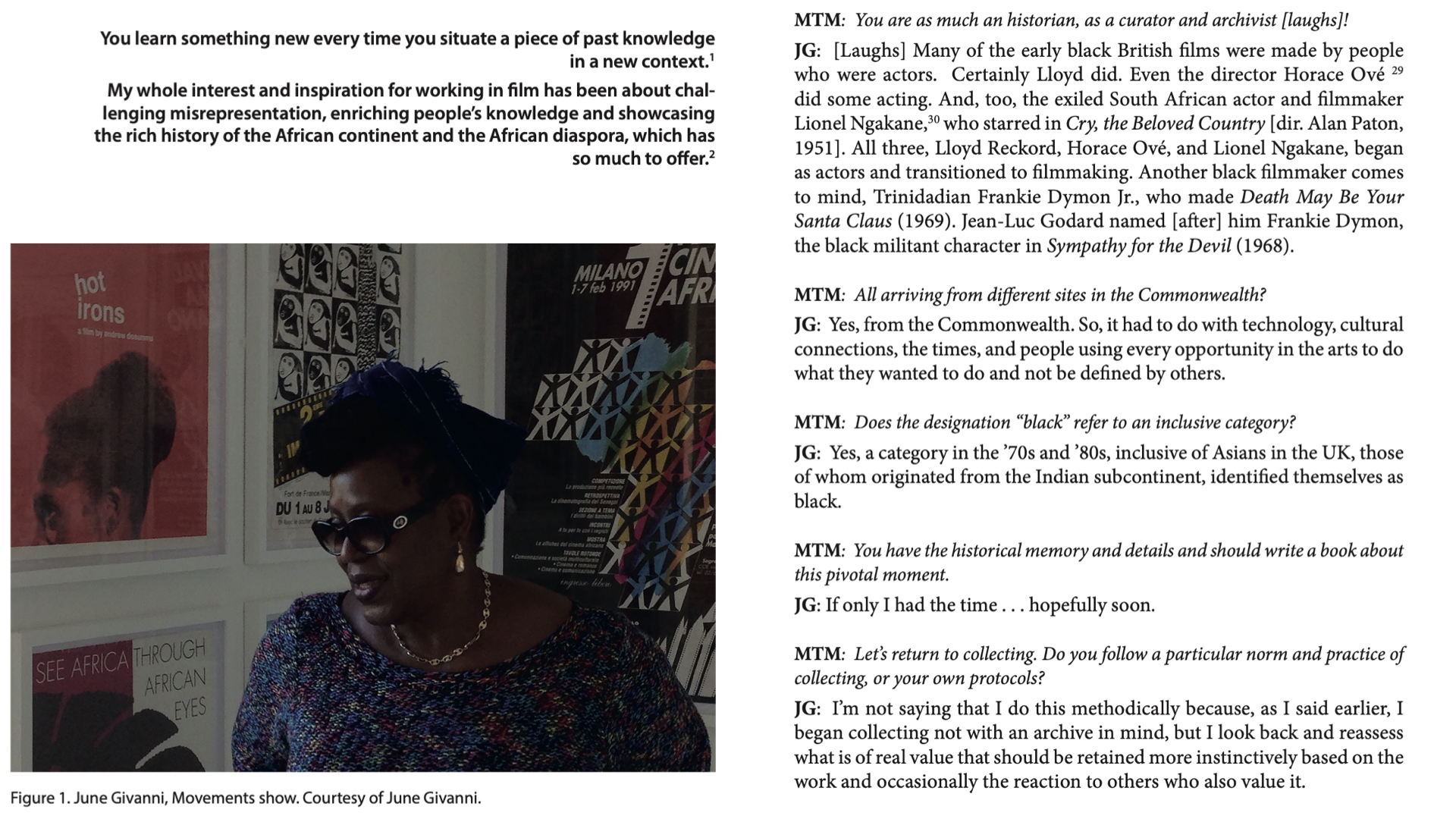

June Givanni

June Givanni is a pioneering international film curator who has considerable experience in film and broadcasting for over 30 years and she is regarded as a resource for African and African diaspora cinema. (June Givanni's story / Pan African Cinema Archive)

Martin T. Michael: You are as much an historian, as a curator and archivist [laughs]!

June Givanni: [Laughs] Many of the early black British films were made by people who were actors. Certainly Lloyd did. Even the director Horace Ové did some acting. And, too, the exiled South African actor and filmmaker Lionel Ngakane, who starred in Cry, the Beloved Country [dir. Alan Paton, 1951]. All three, Lloyd Reckord, Horace Ové, and Lionel Ngakane, began as actors and transitioned to filmmaking. Another black filmmaker comes to mind, Trinidadian Frankie Dymon Jr., who made Death May Be Your Santa Claus (1969). Jean-Luc Godard named [after] him Frankie Dymon, the black militant character in Sympathy for the Devil (1968).

MTM: All arriving from different sites in the Commonwealth?

JG: Yes, from the Commonwealth. So, it had to do with technology, cultural connections, the times, and people using every opportunity in the arts to do what they wanted to do and not be defined by others.

MTM: Does the designation “black” refer to an inclusive category?

JG: Yes, a category in the ’70s and ’80s, inclusive of Asians in the UK, those of whom originated from the Indian subcontinent, identified themselves as black.

MTM: You have the historical memory and details and should write a book about this pivotal moment.

JG: If only I had the time . . . hopefully soon.

MTM: Let’s return to collecting. Do you follow a particular norm and practice of collecting, or your own protocols?

JG: I’m not saying that I do this methodically because, as I said earlier, I began collecting not with an archive in mind, but I look back and reassess what is of real value that should be retained more instinctively based on the work and occasionally the reaction to others who also value it.

Martin, Michael T. "The Practice of Curating the June Givanni Pan African Cinema Archive: A Conversation with the Founding Director." Black Camera 11, no. 1 (2019): 40-61.

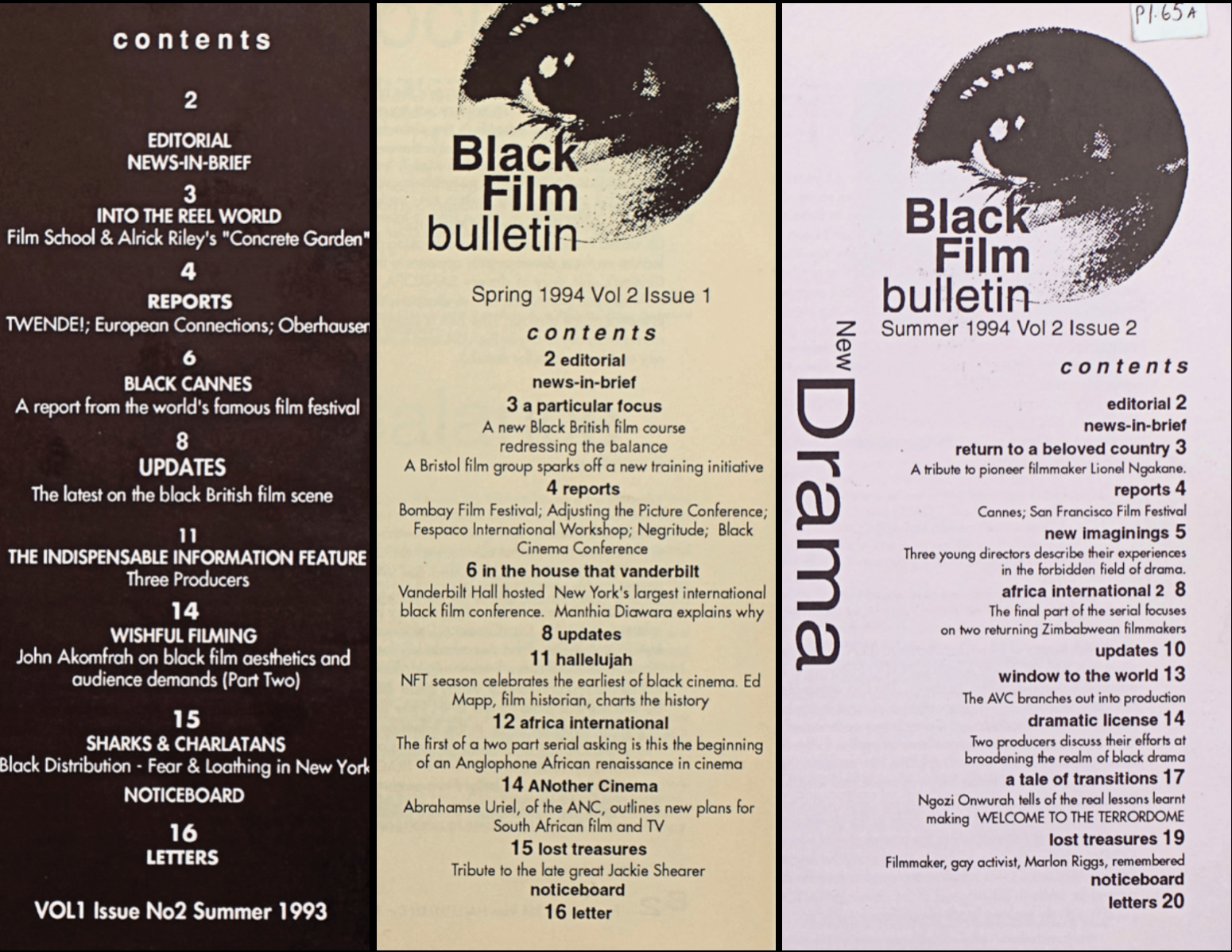

“It was a guerrilla activity”: an oral history of the Black Film Bulletin

"The Black Film Bulletin was first published by the BFI in 1993. Founded by editors June Givanni and Gaylene Gould, it was a vital space for critical commentary around developments in new Black cinema and pan-African cinema histories. Publication ceased around the turn of the millennium, but in recent years the BFB has taken gradual steps to being revived in a new form, this time guided by two members of a new generation – Jan Asante and Melanie Hoyes. All four BFB editors talk James Bell through the Bulletin’s history." October 2020, bfi.org.uk.

[...]

Gaylene Gould: The first thing to say is that I was fan-girling over June while I was a student at Leicester Polytechnic doing a degree in arts administration. I’d been interested in the period of cinema June was talking about – the 80s, the connections between politics and social practice and people like John Akomfrah, Isaac Julien, Sankofa [Film and Video Collective] and the rest. I did my dissertation on that. This was when June had started at the BFI, and I used to call her so she could give me quotes for my dissertation.

So when the job came up at the Unit in 1992, I was like, “This is the only job I can have.” It was an honour to work with June, someone who even back then had this great repository of knowledge and ideas.

We had this brilliant, expansive brief at the Unit, which was to go and discover things. Our international connections were right through what we did – June’s background was so much in pan-Africanism, which was incredibly strong at the time. So there were these conversations happening by phone between us, people in Africa, the States, the Caribbean… and information continually being exchanged. Processing and sharing information became a huge part of our workload, so it felt like a bulletin was needed.

June Givanni: There wasn’t a magazine that was responsive to the energy that was coming through in Black independent cinema – not in the UK, anyway. One of my inspirations was the Black Film Review in the US [a quarterly that ran from 1984-95]. I had written in it; I had been interviewed by it and I was very inspired by it. They were the first ones that were writing about Black film internationally. The editors on it were really established writers, like Clyde Taylor, and – towards the end of the magazine’s life – the late, irrepressible Jacquie Jones.

The Black Film Review was our inspiration, but the BFB was actually set up as a way of responding to the demands on the Unit. The Unit was like a clearing house for everything that was happening around Black film. It got to a stage where there was so much going on that we needed a vehicle, a forum that would be able to share this information. That is why you will see the early Black Film Bulletins had a lot of information sections in addition to features and reviews.

Gaylene Gould: We were down the corridor from Sight & Sound at the time, but we had no idea how to put a magazine together properly! June and I would sit down, and think about what to respond to, what were the hotspots. The bigger double issues we planned more in advance, but on the whole it was responsive.

That all happened in our tiny office, but the great thing about a Black network, or a network of quote-unquote ‘marginalised’ groups, is that there is a network – people are connected. You’d pick up the phone, say, “Hey, you were talking about that the other day, do you want to write a piece?” You were part of the scene.

[...]